How shifting from outcome-based testing to internal model analysis allows teams to surface hidden biases and structural weaknesses before they lead to on-road interventions.

In a modular autonomous driving pipeline, a failure is usually a process of elimination: you can point to a missed detection or a bad tracking label and know exactly what went wrong. But End-to-End (E2E) models change the rules. By mapping raw sensor data directly to driving actions, they trade that clear, step-by-step visibility for better scalability.

Collapsing perception and planning into a single neural network fundamentally changes how failures manifest. In E2E systems, failure mechanisms are no longer explicit or traceable to a specific component; instead, they are embedded in the model’s internal representations. This makes it significantly harder to understand when, where, and why the policy breaks down. As these systems mature, ensuring safety requires a shift in focus: we must analyze the internal model structure, not just closed-loop driving outcomes.

Why closed-loop evaluation is not enough

Closed-loop metrics such as success rate, collisions, interventions, remain essential for evaluating end-to-end driving systems. But they primarily capture outcomes, not causes.

In practice, E2E policies fail under specific combinations of visual appearance, geometry, and context. These failures are sparse and structured, and are often masked by aggregate performance numbers. A model can perform well on average while remaining brittle in precisely the edge cases that dominate safety risk.

This creates a diagnostic gap: closed-loop evaluation tells us that a failure occurred, but offers limited insight into the internal conditions that led to it. Bridging this gap requires tools that expose how the model internally organizes driving-relevant scenarios.

Latent space as a debugging lens

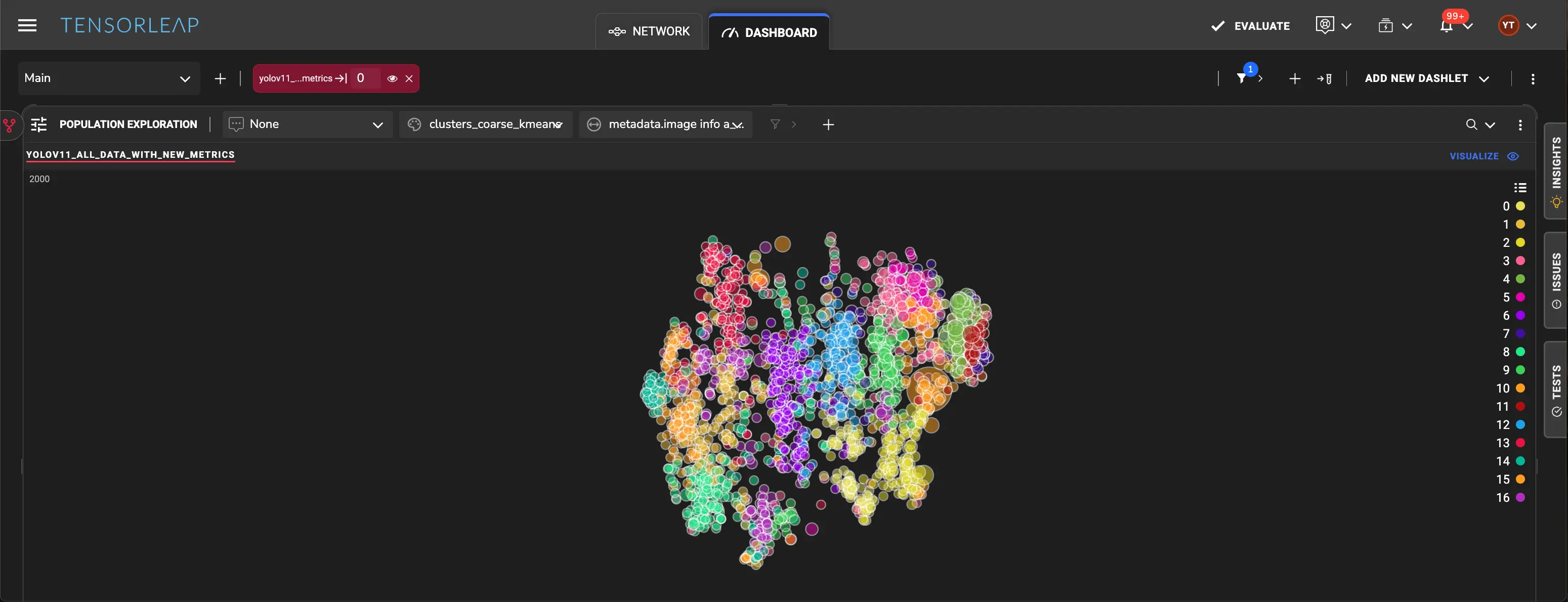

We use latent space analysis to study how failure modes in an end-to-end driving model emerge, organize, and persist.

Our analysis uses the PlanKD implementation of Interfuser, a multi-input transformer-based end-to-end driving model trained and evaluated in the CARLA simulator. To study robustness to sensor variation, we also include data from the Bench2Drive (B2D) dataset, which is CARLA-native but employs a different sensor configuration. This allows us to analyze how sensor-induced domain gaps are reflected in the model’s latent representations.

Exploring failure structure in end-to-end driving models

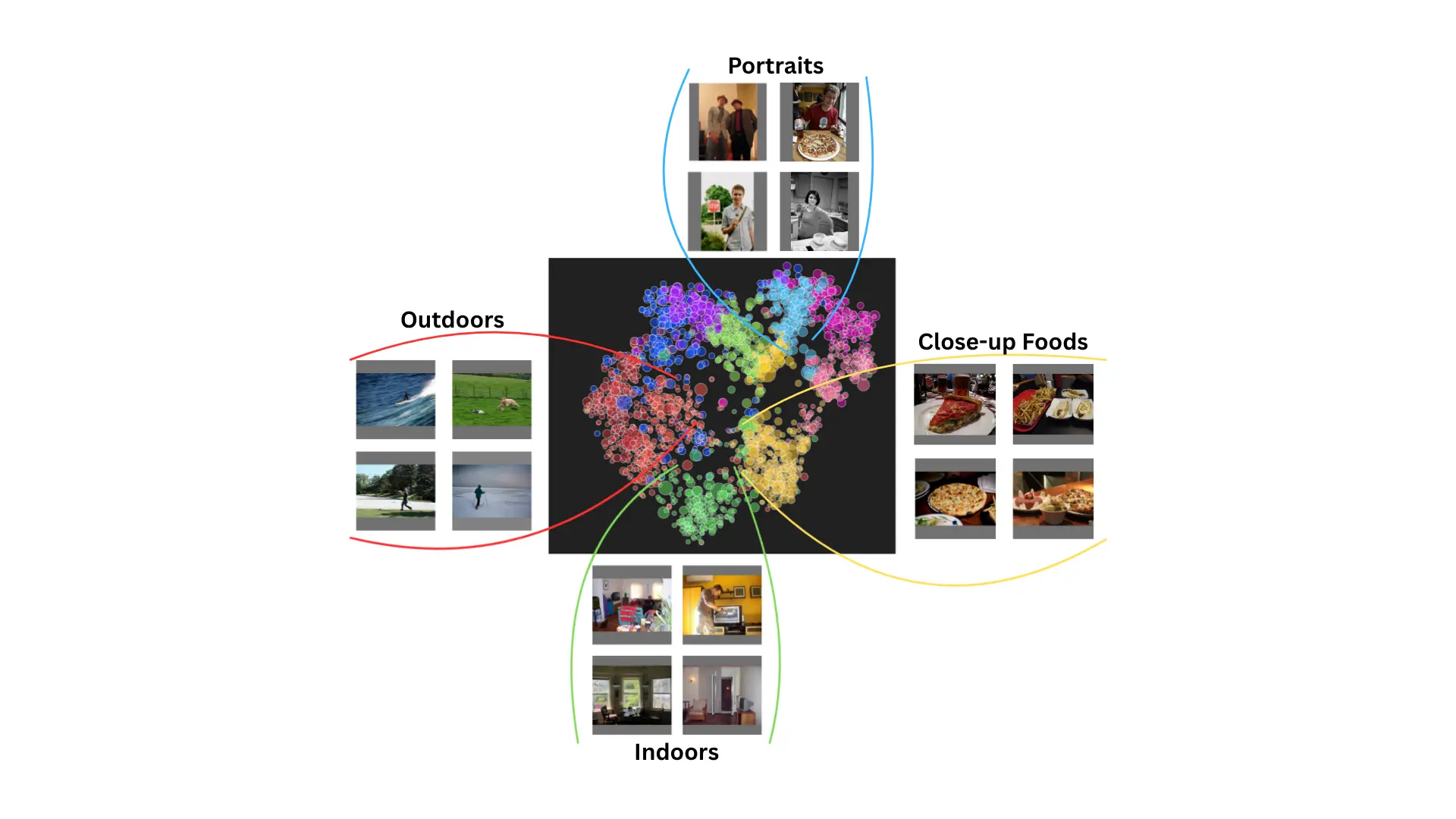

Exploring a model’s latent space gives a direct view into how it organizes driving-relevant concepts and where that organization begins to break down.

Semantic structure and failure regions

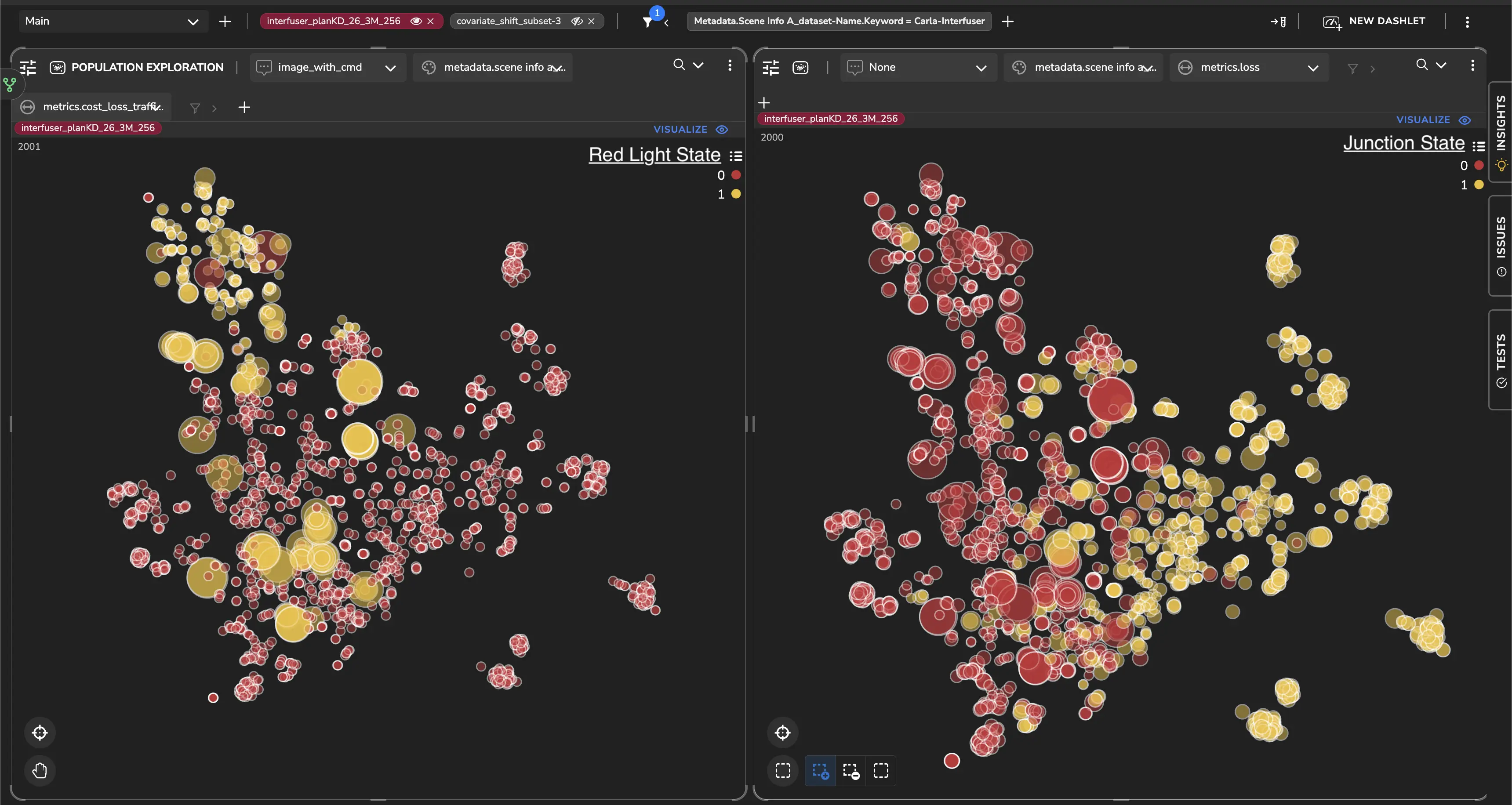

We start by looking at how the model’s latent space organizes related but distinct semantic concepts. Figure 1 visualizes the same latent space under two different semantic overlays: scenes containing red traffic lights, and scenes in which the ego vehicle is inside a junction.

In the red-light view, we’ve seen that these scenes form a compact cluster, suggesting the model has learned a coherent internal representation for this concept. At the same time, red-light scenes that fall outside this cluster consistently show higher traffic-light prediction loss.

What stands out is that these failures are not random outliers. They emerge when visual or geometric variations violate the model’s learned invariances, pushing scenes outside the region of representation space where the policy is well supported by training data.

Figure 1. Latent structure of red traffic light scenes: Side-by-side latent-space visualizations highlighting different semantic attributes. Left: scenes containing red traffic lights (yellow markers). Right: scenes in which the ego vehicle is inside a junction (yellow markers). In the red-light view, samples outside the main cluster correspond to higher traffic-light loss, revealing structured failure regions rather than isolated errors.

Behavioral organization: trajectory geometry

Latent space structure also reveals how the model organizes driving behavior. By probing activations immediately before waypoint prediction, we’ve seen a clear separation between left-turning, straight, and right-turning trajectories.

Within each trajectory regime, the latent space is smoothly ordered by target distance, forming a continuous progression from near to far waypoints. This shows that the model encodes both trajectory geometry and planning horizon in a structured way, largely independent of explicit navigation commands.

One notable detail is that left and right turns are not represented symmetrically. These asymmetries likely reflect biases introduced by driving rules and data collection, for example, differences in turn frequency, yielding behavior, and interaction patterns. Making these biases visible at the representation level provides concrete guidance for targeted evaluation and data balancing.

.webp)

Domain gap in end-to-end autonomous driving

In end-to-end driving systems, perception and control are learned jointly, tightly coupling internal representations to the sensor configuration used during training. Changes in camera placement, resolution, field of view, or LiDAR sampling induce structured shifts in latent space, even when the environment and task remain the same.

This effect becomes clear when comparing representations derived from Interfuser and Bench2Drive data. Although both are CARLA-native and target similar driving tasks, their different sensor configurations lead to systematic differences in visibility and spatial sampling, which show up as a clear separation in latent space.

At the representation level, domain gap analysis shifts the focus from whether a model fails to why it fails, enabling earlier identification of sensor-induced biases before they surface as closed-loop performance degradation.

.webp)

Covariate shift in imitation learning

A fundamental challenge in imitation learning (IL) stems from how supervision is structured. Policies are trained on expert demonstrations that cover only a narrow subset of the state–action space. While perception may generalize broadly, action supervision remains sparse and localized around expert trajectories.

Although covariate shift formally emerges only at deployment time, its root cause can be identified offline through representation-level analysis.

By comparing latent spaces extracted from different depths of the network, we’ve seen cases that lie well within the dense training distribution at early encoder layers but appear as clear outliers near the waypoint predictor. This perceptual–action mismatch highlights states where the model recognizes the scene but lacks reliable action grounding, making it especially vulnerable to compounding errors during closed-loop execution.

Because this failure mode arises from the encoder–decoder structure and action-level supervision inherent to IL, it persists across datasets and architectures.

.webp)

Long-tail failures from spurious visual correlations

End-to-end policies implicitly assume that visual correlations learned during training will generalize at deployment. In the long tail, this assumption can break down.

Latent space analysis reveals a small cluster of red-light scenes associated with disproportionately high prediction loss. This cluster is not town-specific, pointing to a recurring contextual pattern rather than an environment-dependent artifact. Looking at scene metadata and images, we’ve seen strong associations with specific weather conditions and repeated co-occurrence of red traffic lights with other visually salient red objects near intersections.

In these cases, the model allocates disproportionate attention to irrelevant red features, sometimes at the expense of dynamic agents such as pedestrians.

.webp)

To isolate this effect, we compare two CARLA junction scenes generated under the same weather condition with similar traffic configurations. The primary difference between the scenes is the presence of a red object near the intersection. Despite minimal changes, the model’s feature emphasis shifts toward the red object, accompanied by a sharp increase in traffic-related prediction loss.

This example captures a characteristic long-tail failure mode: it affects a small fraction of scenes, emerges only under specific visual configurations, and remains largely invisible to aggregate performance metrics despite its safety relevance.

From reactive testing to proactive debugging

Failures in end-to-end autonomous driving systems are rarely random; they are the structured results of subtle representation gaps, domain shifts, or supervision limitations. Because E2E models consolidate perception and planning, these failure mechanisms don't appear as discrete component errors. Instead, they exist as complex patterns within the model’s internal logic, making them difficult to isolate through standard outcome-based testing.

Ultimately, debugging end-to-end autonomous driving models requires shifting from reactive closed-loop testing to proactive internal analysis.

By surfacing hidden failure patterns like covariate shift and spurious correlations before they manifest on the road, engineering teams can move away from the "trial-and-error" cycle of simulation and toward a precision-driven strategy for data curation and model iteration.

This representation-first explainability approach is central to how we think about debugging complex end-to-end systems at Tensorleap: making internal model behavior observable, comparable, and actionable so issues can be addressed before they surface in closed-loop driving.

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)